Planetary Nebulae

When Sun-like stars get old, they become cooler and redder, increasing their sizes and energy output tremendously: they are called red giants. Most of the carbon (the basis of life) and particulate matter (crucial building blocks of solar systems like ours) in the universe is manufactured and dispersed by red giant stars. When the red giant star has ejected all of its outer layers, the ultraviolet radiation from the exposed hot stellar core makes the surrounding cloud of matter created during the red giant phase glow: the object becomes a planetary nebula. A long-standing puzzle is how planetary nebulae acquire their complex shapes and symmetries, since red giants and the gas/dust clouds surrounding them are mostly round. Hubble's ability to see very fine structural details (usually blurred beyond recognition in ground-based images) enables us to look for clues to this puzzle.

The Glowing Pool Nebula

NGC 3132 is a striking example of a planetary nebula. This expanding cloud of gas, surrounding a dying star, is known to amateur astronomers in the southern hemisphere as the "Eight-Burst" or the "Southern Ring" Nebula.

The name "planetary nebula" refers only to the round shape that many of these objects show when examined through a small visual telescope. In reality, these nebulae have little or nothing to do with planets, but are instead huge shells of gas ejected by stars as they near the ends of their lifetimes. NGC 3132 is nearly half a light year in diameter, and at a distance of about 2000 light years is one of the nearer known planetary nebulae. The gases are expanding away from the central star at a speed of 9 miles per second.

This image, captured by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, clearly shows two stars near the center of the nebula, a bright white one, and an adjacent, fainter companion to its upper right. (A third, unrelated star lies near the edge of the nebula.) The faint partner is actually the star that has ejected the nebula. This star is now smaller than our own Sun, but extremely hot. The flood of ultraviolet radiation from its surface makes the surrounding gases glow through fluorescence. The brighter star is in an earlier stage of stellar evolution, but in the future it will probably eject its own planetary nebula.

In the Heritage Team's rendition of the Hubble image, the colors were chosen to represent the temperature of the gases. Blue represents the hottest gas, which is confined to the inner region of the nebula. Red represents the coolest gas, at the outer edge. The Hubble image also reveals a host of filaments, including one long one that resembles a waistband, made out of dust particles which have condensed out of the expanding gases. The dust particles are rich in elements such as carbon. Eons from now, these particles may be incorporated into new stars and planets when they form from interstellar gas and dust. Our own Sun may eject a similar planetary nebula some 6 billion years from now.

The Cat's Eye Nebula

Acknowledgment: R. Corradi (Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes, Spain) and Z. Tsvetanov (NASA)

In this detailed view from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, the so-called Cat's Eye Nebula looks like the penetrating eye of the disembodied sorcerer Sauron from the film adaptation of "The Lord of the Rings."

The nebula, formally cataloged NGC 6543, is every bit as inscrutable as the J.R.R. Tolkien phantom character. Though the Cat's Eye Nebula was one of the first planetary nebulae to be discovered, it is one of the most complex such nebulae seen in space. A planetary nebula forms when Sun-like stars gently eject their outer gaseous layers that form bright nebulae with amazing and confounding shapes.

In 1994, Hubble first revealed NGC 6543's surprisingly intricate structures, including concentric gas shells, jets of high-speed gas, and unusual shock-induced knots of gas.

As if the Cat's Eye itself isn't spectacular enough, this new image taken with Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) reveals the full beauty of a bull's eye pattern of eleven or even more concentric rings, or shells, around the Cat's Eye. Each 'ring' is actually the edge of a spherical bubble seen projected onto the sky — that's why it appears bright along its outer edge.

Observations suggest the star ejected its mass in a series of pulses at 1,500-year intervals. These convulsions created dust shells, each of which contain as much mass as all of the planets in our solar system combined (still only one percent of the Sun's mass). These concentric shells make a layered, onion-skin structure around the dying star. The view from Hubble is like seeing an onion cut in half, where each skin layer is discernible.

Until recently, it was thought that such shells around planetary nebulae were a rare phenomenon. However, Romano Corradi (Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes, Spain) and collaborators, in a paper published in the European journal Astronomy and Astrophysics in April 2004, have instead shown that the formation of these rings is likely to be the rule rather than the exception.

The bull's-eye patterns seen around planetary nebulae come as a surprise to astronomers because they had no expectation that episodes of mass loss at the end of stellar lives would repeat every 1,500 years. Several explanations have been proposed, including cycles of magnetic activity somewhat similar to our own Sun's sunspot cycle, the action of companion stars orbiting around the dying star, and stellar pulsations. Another school of thought is that the material is ejected smoothly from the star, and the rings are created later on due to formation of waves in the outflowing material. It will take further observations and more theoretical studies to decide between these and other possible explanations.

Approximately 1,000 years ago the pattern of mass loss suddenly changed, and the Cat's Eye Nebula started forming inside the dusty shells. It has been expanding ever since, as discernible in comparing Hubble images taken in 1994, 1997, 2000, and 2002. The puzzle is what caused this dramatic change? Many aspects of the process that leads a star to lose its gaseous envelope are still poorly known, and the study of planetary nebulae is one of the few ways to recover information about these last few thousand years in the life of a Sun-like star.

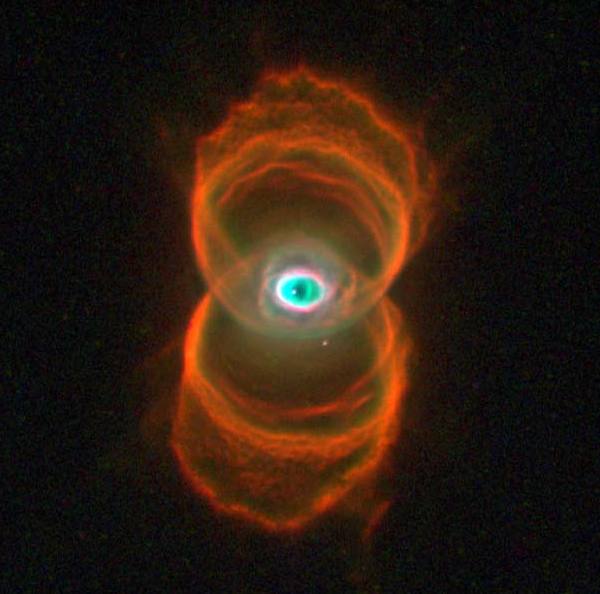

The Hourglass Nebula

This is an image of MyCn18, a young planetary nebula located about 8,000 light-years away, taken with the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) aboard NASA's Hubble Space Telescope (HST). This Hubble image reveals the true shape of MyCn18 to be an hourglass with an intricate pattern of "etchings" in its walls. This picture has been composed from three separate images taken in the light of ionized nitrogen (represented by red), hydrogen (green), and doubly-ionized oxygen (blue). The results are of great interest because they shed new light on the poorly understood ejection of stellar matter which accompanies the slow death of Sun-like stars. In previous ground-based images, MyCn18 appears to be a pair of large outer rings with a smaller central one, but the fine details cannot be seen.

According to one theory for the formation of planetary nebulae, the hourglass shape is produced by the expansion of a fast stellar wind within a slowly expanding cloud which is more dense near its equator than near its poles. What appears as a bright elliptical ring in the center, and at first sight might be mistaken for an equatorially dense region, is seen on closer inspection to be a potato shaped structure with a symmetry axis dramatically different from that of the larger hourglass. The hot star which has been thought to eject and illuminate the nebula, and therefore expected to lie at its center of symmetry, is clearly off center. Hence MyCn18, as revealed by Hubble, does not fulfill some crucial theoretical expectations.

Hubble has also revealed other features in MyCn18 which are completely new and unexpected. For example, there is a pair of intersecting elliptical rings in the central region which appear to be the rims of a smaller hourglass. There are the intricate patterns of the etchings on the hourglass walls. The arc-like etchings could be the remnants of discrete shells ejected from the star when it was younger (e.g. as seen in the Egg Nebula), flow instabilities, or could result from the action of a narrow beam of matter impinging on the hourglass walls. An unseen companion star and accompanying gravitational effects may well be necessary in order to explain the structure of MyCn18.

The Ring Nebula

The NASA Hubble Space Telescope has captured the sharpest view yet of the most famous of all planetary nebulae: the Ring Nebula (M57). In this October 1998 image, the telescope has looked down a barrel of gas cast off by a dying star thousands of years ago. This photo reveals elongated dark clumps of material embedded in the gas at the edge of the nebula; the dying central star floating in a blue haze of hot gas. The nebula is about a light-year in diameter and is located some 2,000 light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Lyra.

The colors are approximately true colors. The color image was assembled from three black-and-white photos taken through different color filters with the Hubble telescope's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2. Blue isolates emission from very hot helium, which is located primarily close to the hot central star. Green represents ionized oxygen, which is located farther from the star. Red shows ionized nitrogen, which is radiated from the coolest gas, located farthest from the star. The gradations of color illustrate how the gas glows because it is bathed in ultraviolet radiation from the remnant central star, whose surface temperature is a white-hot 216,000 degrees Fahrenheit (120,000 degrees Celsius).

The Spirograph Nebula

Acknowledgement: Dr. Raghvendra Sahai (JPL) and Dr. Arsen R. Hajian (USNO)

Glowing like a multi-faceted jewel, the planetary nebula IC 418 lies about 2,000 light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Lepus. This photograph is one of the latest from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, obtained with the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2.

A planetary nebula represents the final stage in the evolution of a star similar to our Sun. The star at the center of IC 418 was a red giant a few thousand years ago, but then ejected its outer layers into space to form the nebula, which has now expanded to a diameter of about 0.1 light-year. The stellar remnant at the center is the hot core of the red giant, from which ultraviolet radiation floods out into the surrounding gas, causing it to fluoresce. Over the next several thousand years, the nebula will gradually disperse into space, and then the star will cool and fade away for billions of years as a white dwarf. Our own Sun is expected to undergo a similar fate, but fortunately this will not occur until some 5 billion years from now.

The Hubble image of IC 418 is shown in a false-color representation, based on Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 exposures taken in February and September, 1999 through filters that isolate light from various chemical elements. Red shows emission from ionized nitrogen (the coolest gas in the nebula, located furthest from the hot nucleus), green shows emission from hydrogen, and blue traces the emission from ionized oxygen (the hottest gas, closest to the central star). The remarkable textures seen in the nebula are newly revealed by the Hubble telescope, and their origin is still uncertain.

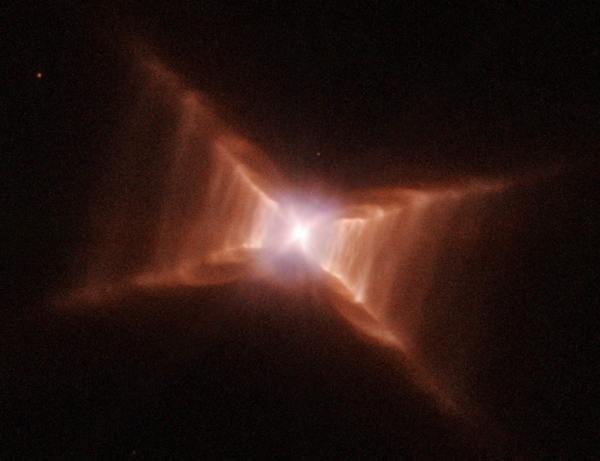

The Red Rectangle

Astronomers may not have observed the fabled "Stairway to Heaven," but they have photographed something almost as intriguing: ladder-like structures surrounding a dying star.

A new image, taken with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, reveals startling new details of one of the most unusual nebulae known in our Milky Way. Cataloged as HD 44179, this nebula is more commonly called the "Red Rectangle" because of its unique shape and color as seen with ground-based telescopes.

Hubble has revealed a wealth of new features in the Red Rectangle that cannot be seen with ground-based telescopes looking through the Earth's turbulent atmosphere. Details of the Hubble study were published in the April 2004 issue of The Astronomical Journal.

Hubble's sharp pictures show that the Red Rectangle is not really rectangular, but has an overall X-shaped structure, which the astronomers involved in the study interpret as arising from outflows of gas and dust from the star in the center. The outflows are ejected from the star in two opposing directions, producing a shape like two ice-cream cones touching at their tips. Also remarkable are straight features that appear like rungs on a ladder, making the Red Rectangle look similar to a spider web, a shape unlike that of any other known nebula in the sky. These rungs may have arisen in episodes of mass ejection from the star occurring every few hundred years. They could represent a series of nested, expanding structures similar in shape to wine glasses, seen exactly edge-on so that their rims appear as straight lines from our vantage point.

The star in the center of the Red Rectangle is one that began its life as a star similar to our Sun. It is now nearing the end of its lifetime, and is in the process of ejecting its outer layers to produce the visible nebula. The shedding of the outer layers began about 14,000 years ago. In a few thousand years, the star will have become smaller and hotter, and will begin to release a flood of ultraviolet light into the surrounding nebula; at that time, gas in the nebula will begin to fluoresce, producing what astronomers call a planetary nebula.

At the present time, however, the star is still so cool that atoms in the surrounding gas do not glow, and the surrounding dust particles can only be seen because they are reflecting the starlight from the central star. In addition, there are molecules mixed in with the dust, which emit light in the red portion of the spectrum. Astronomers are not yet certain which types of molecules are producing the red color that is so striking in the Red Rectangle, but suspect that they are hydrocarbons that form in the cool outflow from the central star.

Another remarkable feature of the Red Rectangle, visible only with the superb resolution of the Hubble telescope, is the dark band passing across the central star. This dark band is the shadow of a dense disk of dust that surrounds the star. In fact, the star itself cannot be seen directly, due to the thickness of the dust disk. All we can see is light that streams out perpendicularly to the disk, and then scatters off of dust particles toward our direction. Astronomers found that the star in the center is actually a close pair of stars that orbit each other with a period of about 10 1/2 months. Interactions between these stars have probably caused the ejection of the thick dust disk that obscures our view of the binary. The disk has funneled subsequent outflows in the directions perpendicular to the disk, forming the bizarre bi- conical structure we see as the Red Rectangle. The reasons for the periodic ejections of more gas and dust, which are producing the "rungs" revealed in the Hubble image, remain unknown.

The Red Rectangle was first discovered during a rocket flight in the early 1970s, in which astronomers were searching for strong sources of infrared radiation. This infrared source lies about 2,300 light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Monoceros. Stars surrounded by clouds of dust are often strong infrared sources because the dust is heated by the starlight and radiates long-wavelength light. Studies of HD 44179 with ground-based telescopes revealed a rectangular shape in the dust surrounding the star in the center, leading to the name Red Rectangle which was coined in 1973 by astronomers Martin Cohen and Mike Merrill.

This image was made from observations taken on March 17-18, 1999 with Hubble's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2.

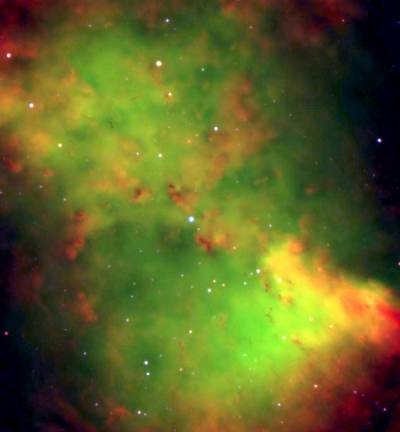

NGC 2440

The central star of NGC 2440 is one of the hottest known, with a surface temperature near 200,000 degrees Celsius. The complex structure of the surrounding nebula suggests to some astronomers that there have been periodic oppositely directed outflows from the central star, somewhat similar to that in NGC 2346, but in the case of NGC 2440 these outflows have been episodic, and in different directions during each episode.

The nebula is also rich in clouds of dust, some of which form long, dark streaks pointing away from the central star. In addition to the bright nebula, which glows because of fluorescence due to ultraviolet radiation from the hot star, NGC 2440 is surrounded by a much larger cloud of cooler gas which is invisible in ordinary light but can be detected with infrared telescopes. NGC 2440 lies about 4,000 light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Puppis.

The Hubble Heritage team made this image from observations of NGC 2440 acquired by Howard Bond (STScI) and Robin Ciardullo (Penn State).

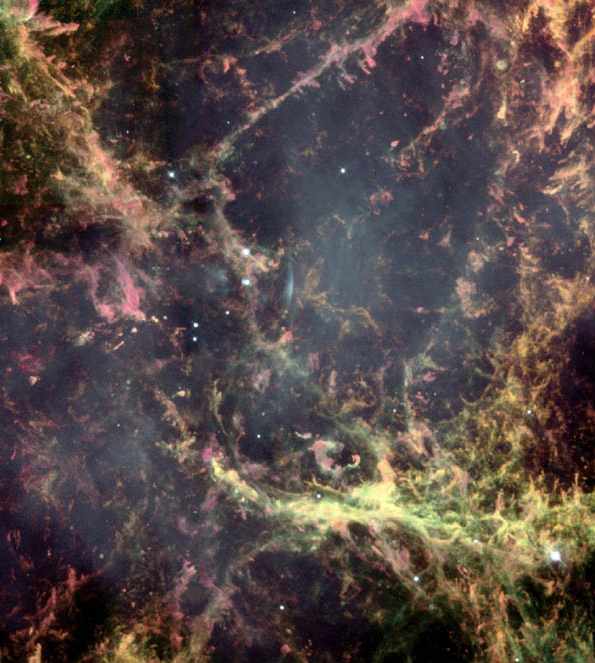

Peering into the Heart of the Crab Nebula

Acknowledgement: W. P. Blair (JHU)

In the year 1054 A.D., Chinese astronomers were startled by the appearance of a new star, so bright that it was visible in broad daylight for several weeks. Today, the Crab Nebula is visible at the site of the "Guest Star". Located about 6,500 light-years from Earth, the Crab Nebula is the remnant of a star that began its life with about 10 times the mass of our own Sun. Its life ended on July 4, 1054 when it exploded as a supernova. In this image, NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has zoomed in on the center of the Crab to reveal its structure with unprecedented detail.

The Crab Nebula data were obtained by Hubble's Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 in 1995. Images taken with five different color filters have been combined to construct this new false-color picture. Resembling an abstract painting by Jackson Pollack, the image shows ragged shreds of gas that are expanding away from the explosion site at over 3 million miles per hour.

The core of the star has survived the explosion as a "pulsar," visible in the Hubble image as the lower of the two moderately bright stars to the upper left of center. The pulsar is a neutron star that spins on its axis 30 times a second. It heats its surroundings, creating the ghostly diffuse bluish-green glowing gas cloud in its vicinity, including a blue arc just to its right.

The colorful network of filaments is the material from the outer layers of the star that was expelled during the explosion. The picture is somewhat deceptive in that the filaments appear to be close to the pulsar. In reality, the yellowish green filaments toward the bottom of the image are closer to us, and approaching at some 300 miles per second. The orange and pink filaments toward the top of the picture include material behind the pulsar, rushing away from us at similar speeds.

The various colors in the picture arise from different chemical elements in the expanding gas, including hydrogen (orange), nitrogen (red), sulfur (pink), and oxygen (green). The shades of color represent variations in the temperature and density of the gas, as well as changes in the elemental composition. These chemical elements, some of them newly created during the evolution and explosion of the star and now blasted back into space, will eventually be incorporated into new stars and planets. Astronomers believe that the chemical elements in the Earth and even in our own bodies, such as carbon, oxygen, and iron, were made in other exploding stars billions of years ago.

The Unveiling of a Planetary Nebula

This HST Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 image captures the infancy of the Stingray Nebula (Hen-1357), the youngest known planetary nebula.

In this image, the bright central star is in the middle of the green ring of gas. Its companion star is diagonally above it at 10 o'clock. A spur of gas (green) is forming a faint bridge to the companion star due to gravitational attraction.

The image also shows a ring of gas (green) surrounding the central star, with bubbles of gas to the lower left and upper right of the ring. The wind of material propelled by radiation from the hot central star has created enough pressure to blow open holes in the ends of the bubbles, allowing gas to escape.

The red curved lines represent bright gas that is heated by a "shock" caused when the central star's wind hits the walls of the bubbles.

The nebula is as large as 130 solar systems, but, at its distance of 18,000 light-years, it appears only as big as a dime viewed a mile away. The Stingray is located in the direction of the southern constellation Ara (the Altar).

The colors shown are actual colors emitted by nitrogen (red), oxygen (green), and hydrogen (blue). The filters used were F658N ([N II]), F502N ([O III]), and F487N (H-beta). The observations were made in March 1996.

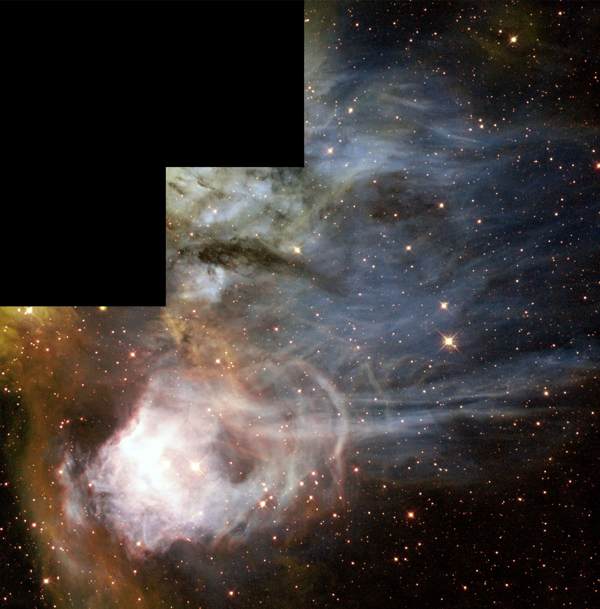

Gaseous Streamers Flutter in Stellar Breeze

Acknowledgment: D. Garnett (University of Arizona)

Resembling the hair in Botticelli's famous portrait of the birth of Venus, softly glowing filaments stream from a complex of hot young stars. This image of a nebula, known as N44C, comes from the archives of NASA's Hubble Space Telescope (HST). It was taken with the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 in 1996 and is being presented by the Hubble Heritage Project.

N44C is the designation for a region of glowing hydrogen gas surrounding an association of young stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a nearby, small companion galaxy to the Milky Way visible from the Southern Hemisphere.

N44C is peculiar because the star mainly responsible for illuminating the nebula is unusually hot. The most massive stars, ranging from 10-50 times more massive than the Sun, have maximum temperatures of 54,000 to 90,000 degrees Fahrenheit (30,000 to 50,000 degrees Kelvin). The star illuminating N44C appears to be significantly hotter, with a temperature of about 135,000 degrees Fahrenheit (75,000 degrees Kelvin)!

Ideas proposed to explain this unusually high temperature include the possibility of a neutron star or black hole that intermittently produces X-rays but is now "switched off."

On the top right of this Hubble image is a network of nebulous filaments that inspired comparison to Botticelli. The filaments surround a Wolf-Rayet star, another kind of rare star characterized by an exceptionally vigorous "wind" of charged particles. The shock of the wind colliding with the surrounding gas causes the gas to glow.

N44C is part of the larger N44 complex, which includes young, hot, massive stars, nebulae, and a "superbubble" blown out by multiple supernova explosions. Part of the superbubble is seen in red at the very bottom left of the HST image.

The data were taken in November 1996 with Hubble's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 by Donald Garnett (University of Arizona) and collaborators and stored in the Hubble archive. The image was composed by the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA).

NGC 6853

The Dumbbell Nebula

The Dumbbell Nebula - also known as Messier 27 or NGC 6853 - is a typical planetary nebula and is located in the constellation Vulpecula (The Fox). The distance is rather uncertain, but is believed to be around 1200 light-years. It was first described by the French astronomer and comet hunter Charles Messier who found it in 1764 and included it as no. 27 in his famous list of extended sky objects [2].

Despite its class, planetary nebula, the Dumbbell Nebula has nothing to do with planets. It consists of very rarified gas that has been ejected from the hot central star (well visible on this photo), now in one of the last evolutionary stages. The gas atoms in the nebula are excited (heated) by the intense ultraviolet radiation from this star and emit strongly at specific wavelengths.

These photos are the beautiful by-product of a technical test of some FORS1 narrow-band optical interference filter. They only allow light in a small wavelength range to pass and are used to isolate emissions from particular atoms and ions. The bottom one is an enlargement that shows well the intricate structure in the central part of the nebula.

In this three-color composite, a short exposure was first made through a wide-band filter registering blue light from the nebula. It was then combined with exposures through two interference filters in the light of double-ionized oxygen atoms and atomic hydrogen. They were color-coded as "blue", "green" and "red", respectively, and then combined to produce this picture that shows the structure of the nebula in "approximately true" colors.

Technical information: Photos are reproduced from a three-color composite based on two interference ([OIII] at 501 nm and 6 nm FWHM - 5 min exposure time; H-alpha at 656 nm and 6 nm FWHM - 5 min) and one broadband (Bessell B at 429 nm and 88 nm FWHM; 30 sec) filter images, obtained on September 28, 1998, during mediocre seeing conditions (0.8 arcsec). The CCD camera has 2048 x 2048 pix, each covering 24 x 24 µm and the sky fields shown measure 6.8 x 6.8 arcmin and 3.5 x 3.9 arcmin, respectively. North is up; East is left.

Close-Up of the Dumbbell Nebula

Acknowledgment: C.R. O'Dell (Vanderbilt University)

An aging star's last hurrah is creating a flurry of glowing knots of gas that appear to be streaking through space in this close-up image of the Dumbbell Nebula, taken with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope.

The Dumbbell, a nearby planetary nebula residing more than 1,200 light-years away, is the result of an old star that has shed its outer layers in a glowing display of color. The nebula, also known as Messier 27 (M27), was the first planetary nebula ever discovered. French astronomer Charles Messier spotted it in 1764.

The Hubble images of the Dumbbell show many knots, but their shapes vary. Some look like fingers pointing at the central star, located just off the upper left of the image; others are isolated clouds, with or without tails. Their sizes typically range from 11 - 35 billion miles (17 - 56 billion kilometers), which is several times larger than the distance from the Sun to Pluto. Each contains as much mass as three Earths.

The knots are forming at the interface between the hot (ionized) and cool (neutral) portion of the nebula. This area of temperature differentiation moves outward from the central star as the nebula evolves. In the Dumbbell astronomers are seeing the knots soon after this hot gas passed by.

Dense knots of gas and dust seem to be a natural part of the evolution of planetary nebulae. They form in the early stages, and their shape changes as the nebula expands. Similar knots have been discovered in other nearby planetary nebulae that are all part of the same evolutionary scheme. They can be seen in Hubble telescope photos of the Ring Nebula (NGC 6720), the Eskimo Nebula (NGC 2392) and the Retina Nebula (IC 4406). The detection of these knots in all the nearby planetaries imaged by the Hubble telescope allows astronomers to hypothesize that knots may be a feature common in all planetary nebulae.

This image, created by the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI), was taken by Hubble's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 in November 2001, by Bob O'Dell (Vanderbilt University) and collaborators. The filters used to create this color image show oxygen in blue, hydrogen in green and a combination of sulfur and nitrogen emission in red.

Beauty in the Eye of Hubble

Acknowledgment: C.R. O'Dell (Vanderbilt University)

Like many other so-called planetary nebulae, IC 4406 exhibits a high degree of symmetry; the left and right halves of the Hubble image are nearly mirror images of the other. If we could fly around IC4406 in a starship, we would see that the gas and dust form a vast donut of material streaming outward from the dying star. From Earth, we are viewing the donut from the side. This side view allows us to see the intricate tendrils of dust that have been compared to the eye's retina. In other planetary nebulae, like the Ring Nebula (NGC 6720), we view the donut from the top.

The donut of material confines the intense radiation coming from the remnant of the dying star. Gas on the inside of the donut is ionized by light from the central star and glows. Light from oxygen atoms is rendered blue in this image; hydrogen is shown as green, and nitrogen as red. The range of color in the final image shows the differences in concentration of these three gases in the nebula.

Unseen in the Hubble image is a larger zone of neutral gas that is not emitting visible light, but which can be seen by radio telescopes.

One of the most interesting features of IC 4406 is the irregular lattice of dark lanes that criss-cross the center of the nebula. These lanes are about 160 astronomical units wide (1 astronomical unit is the distance between the Earth and Sun). They are located right at the boundary between the hot glowing gas that produces the visual light imaged here and the neutral gas seen with radio telescopes. We see the lanes in silhouette because they have a density of dust and gas that is a thousand times higher than the rest of the nebula. The dust lanes are like a rather open mesh veil that has been wrapped around the bright donut.

The fate of these dense knots of material is unknown. Will they survive the nebula's expansion and become dark denizens of the space between the stars or simply dissipate?

This image is a composite of data taken by Hubble's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 in June 2001 by Bob O'Dell (Vanderbilt University) and collaborators and in January 2002 by The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI). Filters used to create this color image show oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen gas glowing in this object.

Supersonic Exhaust from Nebula

M2-9 is a striking example of a "butterfly" or a bipolar planetary nebula. Another more revealing name might be the "Twin Jet Nebula." If the nebula is sliced across the star, each side of it appears much like a pair of exhausts from jet engines. Indeed, because of the nebula's shape and the measured velocity of the gas, in excess of 200 miles per second, astronomers believe that the description as a super-super-sonic jet exhaust is quite apt. Ground-based studies have shown that the nebula's size increases with time, suggesting that the stellar outburst that formed the lobes occurred just 1,200 years ago.

The central star in M2-9 is known to be one of a very close pair which orbit one another at perilously close distances. It is even possible that one star is being engulfed by the other. Astronomers suspect the gravity of one star pulls weakly bound gas from the surface of the other and flings it into a thin, dense disk which surrounds both stars and extends well into space.

The disk can actually be seen in shorter exposure images obtained with the Hubble telescope. It measures approximately 10 times the diameter of Pluto's orbit. Models of the type that are used to design jet engines ("hydrodynamics") show that such a disk can successfully account for the jet-exhaust-like appearance of M2-9. The high-speed wind from one of the stars rams into the surrounding disk, which serves as a nozzle. The wind is deflected in a perpendicular direction and forms the pair of jets that we see in the nebula's image. This is much the same process that takes place in a jet engine: The burning and expanding gases are deflected by the engine walls through a nozzle to form long, collimated jets of hot air at high speeds.

M2-9 is 2,100 light-years away in the constellation Ophiucus. The observation was taken Aug. 2, 1997 by the Hubble telescope's Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2. In this image, neutral oxygen is shown in red, once-ionized nitrogen in green, and twice-ionized oxygen in blue.

Ant-like Space Structure Previews Death of Our Sun

Acknowledgment: R. Sahai (JPL) and B. Balick (University of Washington)

From ground-based telescopes, the so-called "ant nebula" (Menzel 3, or Mz3) resembles the head and thorax of a garden-variety ant. This dramatic NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope image, showing 10 times more detail, reveals the "ant's" body as a pair of fiery lobes protruding from a dying, Sun-like star.

The Hubble images directly challenge old ideas about the last stages in the lives of stars. By observing Sun-like stars as they approach their deaths, the Hubble Heritage image of Mz3 -- along with pictures of other planetary nebulae -- shows that our Sun's fate probably will be more interesting, complex, and striking than astronomers imagined just a few years ago.

Though approaching the violence of an explosion, the ejection of gas from the dying star at the center of Mz3 has intriguing symmetrical patterns unlike the chaotic patterns expected from an ordinary explosion. Scientists using Hubble would like to understand how a spherical star can produce such prominent, non-spherical symmetries in the gas that it ejects.

One possibility is that the central star of Mz3 has a closely orbiting companion that exerts strong gravitational tidal forces, which shape the outflowing gas. For this to work, the orbiting companion star would have to be close to the dying star, about the distance of the Earth from the Sun. At that distance the orbiting companion star wouldn't be far outside the hugely bloated hulk of the dying star. It's even possible that the dying star has consumed its companion, which now orbits inside of it, much like the duck in the wolf's belly in the story "Peter and the Wolf."

A second possibility is that, as the dying star spins, its strong magnetic fields are wound up into complex shapes like spaghetti in an eggbeater. Charged winds moving at speeds up to 1000 kilometers per second from the star, much like those in our Sun's solar wind but millions of times denser, are able to follow the twisted field lines on their way out into space. These dense winds can be rendered visible by ultraviolet light from the hot central star or from highly supersonic collisions with the ambient gas that excites the material into florescence.

No other planetary nebula observed by Hubble resembles Mz3 very closely. M2-9 comes close, but the outflow speeds in Mz3 are up to 10 times larger than those of M2-9. Interestingly, the very massive, young star, Eta Carinae, shows a very similar outflow pattern.

Astronomers Bruce Balick (University of Washington) and Vincent Icke (Leiden University) used Hubble to observe this planetary nebula, Mz3, in July 1997 with the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2. One year later, astronomers Raghvendra Sahai and John Trauger of the Jet Propulsion Lab in California snapped pictures of Mz3 using slightly different filters. This intriguing image, which is a composite of several filters from each of the two datasets, was created by the Hubble Heritage Team.

CosmicLight.com Home

CosmicLight.com Home