Jupiter

The Ancient Storm in the Atmosphere of Jupiter

When 17th-century astronomers first turned their telescopes to Jupiter, they noted a conspicuous reddish spot on the giant planet. This Great Red Spot is still present in Jupiter's atmosphere, more than 300 years later. It is now known that it is a vast storm, spinning like a cyclone. Unlike a low-pressure hurricane in the Caribbean Sea, however, the Red Spot rotates in a counterclockwise direction in the southern hemisphere, showing that it is a high-pressure system. Winds inside this Jovian storm reach speeds of about 270 mph.

The Red Spot is the largest known storm in the Solar System. With a diameter of 15,400 miles, it is almost twice the size of the entire Earth and one-sixth the diameter of Jupiter itself.

The long lifetime of the Red Spot may be due to the fact that Jupiter is mainly a gaseous planet. It possibly has liquid layers, but lacks a solid surface, which would dissipate the storm's energy, much as happens when a hurricane makes landfall on the Earth. However, the Red Spot does change its shape, size, and color, sometimes dramatically. Such changes are demonstrated in high-resolution Wide Field and Planetary Cameras 1 & 2 images of Jupiter obtained by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, and presented here by the Hubble Heritage Project team. The mosaic presents a series of pictures of the Red Spot obtained by Hubble between 1992 and 1999.

Astronomers study weather phenomena on other planets in order to gain a greater understanding of our own Earth's climate. Lacking a solid surface, Jupiter provides us with a laboratory experiment for observing weather phenomena under very different conditions than those prevailing on Earth. This knowledge can also be applied to places in the Earth's atmosphere that are over deep oceans, making them more similar to Jupiter's deep atmosphere.

The Hubble images were originally collected by Amy Simon (Cornell U.), Reta Beebe (NMSU), Heidi Hammel (Space Science Institute, MIT), and their collaborators, and have been prepared for presentation by the Hubble Heritage Team.

The Red Spot Storm in False Color

False color representation of Jupiter's Great Red Spot taken with Galileo's imaging system through three different near-infrared filters. This is a mosaic of eighteen images (6 in each filter) that were taken over a period of 6 minutes on June 26, 1996.

The Great Red Spot appears pink and the surrounding region blue because of the particular color coding used in this representation. The red channel is the reflectance of Jupiter at a wavelength where methane strongly absorbs (889nm). Because of this absorption, only high clouds can reflect sunlight in this wavelength. The green channel is the reflectance in a wavelength where methane absorbs, but less strongly (727nm). Lower clouds can reflect sunlight in this wavelength. Finally, the blue channel is the reflectance in a wavelength where there are essentially no absorbers in the Jovian atmosphere (756nm) and one sees light reflected from the deepest clouds. Thus, the color of a cloud in this image indicates its height, with red or white being highest and blue or black being lowest.

This image shows the Great Red Spot to be relatively high, as are some smaller clouds to the northeast and northwest that are surprisingly like towering thunderstorms found on earth. The deepest clouds are in the collar surrounding the Great Red Spot, and also just to the northwest of the high (bright) cloud in the northwest corner of the image. Preliminary modeling shows these cloud heights to range about 50km in altitude.

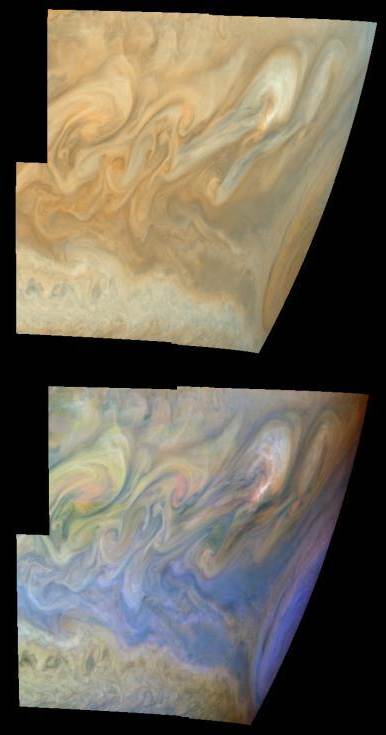

The Turbulent Region Near the Great Spot

These images are true and false color mosaics taken by Galileo of the turbulent region west of Jupiter's Great Red Spot. The Great Red Spot is on the planetary limb on the right hand side of each mosaic. The region west (left) of the Great Red Spot is characterized by large, turbulent structures that rapidly change in appearance. The turbulence results from the collision of a westward jet that is deflected northward by the Great Red Spot into a higher latitude eastward jet. The large eddies nearest to the Great Red Spot are bright, suggesting that convection and cloud formation are active there.

The top mosaic combines the violet (410 nanometers) and near infrared continuum (756 nanometers) filter images to create a mosaic similar to how Jupiter would appear to human eyes. Differences in coloration are due to the composition and abundance of trace chemicals in Jupiter's atmosphere. The lower mosaic uses the Galileo imaging camera's three near-infrared (invisible) wavelengths (756 nanometers, 727 nanometers, and 889 nanometers displayed in red, green, and blue) to show variations in cloud height and thickness. Light blue clouds are high and thin, reddish clouds are deep, and white clouds are high and thick. Purple most likely represents a high haze overlying a clear deep atmosphere. Galileo is the first spacecraft to distinguish cloud layers on Jupiter.

The mosaic is centered at 16.5 degrees south planetocentric latitude and 85 degrees west longitude. The north-south dimension of the Great Red Spot is approximately 11,000 kilometers. The smallest resolved features are tens of kilometers in size. North is at the top of the picture. The images used were taken on June 26, 1997 at a range of 1.2 million kilometers (1.05 million miles) by the Solid State Imaging (SSI) system on NASA's Galileo spacecraft.

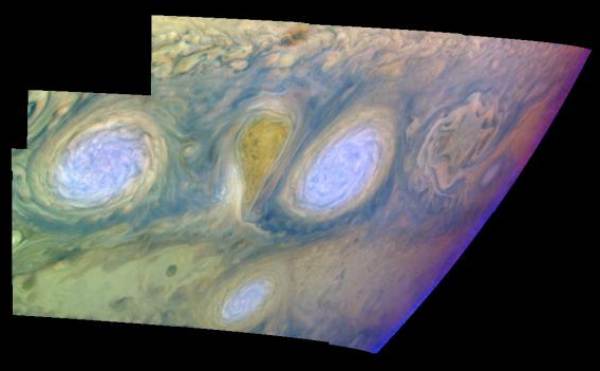

Jupiter's White Ovals

Oval cloud systems of this type are often associated with chaotic cyclonic systems such as the balloon shaped vortex seen here between the well formed ovals. This system is centered near 30 degrees south planetocentric latitude and 100 degrees west longitude and rotates in a clockwise sense about its center. The oval shaped vortices in the upper half of the mosaic are two of the three long-lived White Ovals that formed to the south of the Red Spot in the 1930's and, like the Red Spot, rotate in a counterclockwise sense. The east to west dimension of the leftmost White Oval is 9000 kilometers (km). (The diameter of the Earth is 12,756 km.) The White Ovals drift in longitude relative to one another, and are presently restricting the cyclonic structure.

To the south, the smaller oval and its accompanying cyclonic system are moving eastward at about 0.4 degrees per day relative to the larger ovals. The interaction between these two cyclonic storm systems is producing high, thick cumulus- like clouds in the southern part of the more northerly trapped system.

This mosaic uses the Galileo imaging camera's three near-infrared wavelengths (756 nanometers, 727 nanometers, and 889 nanometers displayed in red, green, and blue) to show variations in cloud height and thickness. Light blue clouds are high and thin, reddish clouds are deep, and white clouds are high and thick. The clouds and haze over the White Ovals are high, extending into Jupiter's stratosphere. There is a lack of high haze over the cylonic feature. Dark purple most likely represents a high haze overlying a clear deep atmosphere. Galileo is the first spacecraft to distinguish cloud layers on Jupiter.

North is at the top of this mosaic. The smallest resolved features are tens of kilometers in size. The planetary limb runs along the right edge of the mosaic. Cloud patterns appear foreshortened as they approach the limb. These images were taken on February 19, 1997, at a range of 1.1 million km by the Solid State Imaging (CCD) system aboard NASA's Galileo spacecraft.

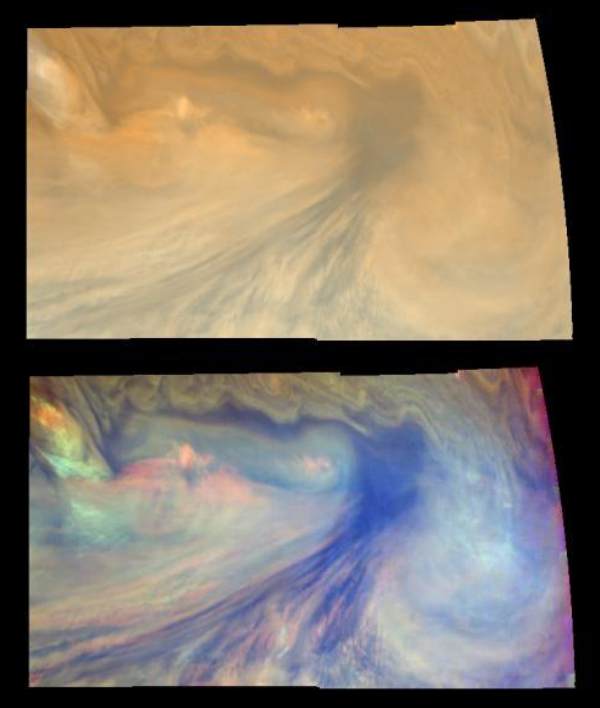

Equatorial Hotspot

These images are true and false color views of an equatorial ‘hotspot’ on Jupiter and cover an area 34,000 kilometers by 11,000 kilometers. The top mosaic combines the violet (410 nanometers or nm) and near-infrared continuum (756 nm) filter images to create an image similar to how Jupiter would appear to human eyes. Differences in coloration are due to the composition and abundances of trace chemicals in Jupiter’s atmosphere. The bottom mosaic uses Galileo’s three near- infrared wavelengths (756 nm, 727 nm, and 889 nm displayed in red, green, and blue) to show variations in cloud height and thickness. Bluish clouds are high and thin, reddish clouds are low, and white clouds are high and thick. The dark blue hotspot in the center is a hole in the deep cloud with an overlying thin haze. The light blue region to the left is covered by a very high haze layer. The multicolored region to the right has overlapping cloud layers of different heights. Galileo is the first spacecraft to distinguish cloud layers on Jupiter.

North is at the top. The mosaics cover latitudes 1 to 10 degrees and are centered at longitude 336 degrees West. The planetary limb runs along the right edge of the image. Cloud patterns appear foreshortened as they approach the limb. The smallest resolved features are tens of kilometers in size. These images were taken on December 17, 1996, at a range of 1.5 million kilometers by the Solid State Imaging system aboard NASA’s Galileo spacecraft.

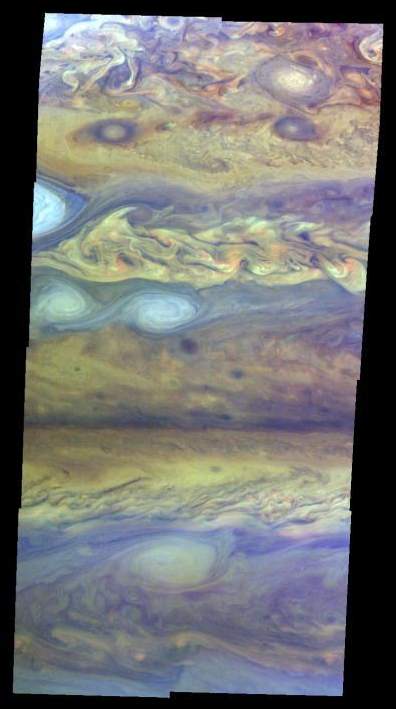

Northern Hemisphere

Mosaic of Jupiter's northern hemisphere between 10 and 50 degrees latitude. Jupiter's atmospheric circulation is dominated by alternating eastward and westward jets from equatorial to polar latitudes. The direction and speed of these jets in part determine the color and texture of the clouds seen in this mosaic. Also visible are several other common Jovian cloud features, including large white ovals, bright spots, dark spots, interacting vortices, and turbulent chaotic systems. The north-south dimension of each of the two interacting vortices in the upper half of the mosaic is about 3500 kilometers.

This mosaic uses the Galileo imaging camera's three near-infrared wavelengths (756 nanometers, 727 nanometers, and 889 nanometers displayed in red, green, and blue) to show variations in cloud height and thickness. Light blue clouds are high and thin, reddish clouds are deep, and white clouds are high and thick. The clouds and haze over the ovals are high, extending into Jupiter's stratosphere. Dark purple most likely represents a high haze overlying a clear deep atmosphere. Galileo is the first spacecraft to distinguish cloud layers on Jupiter.

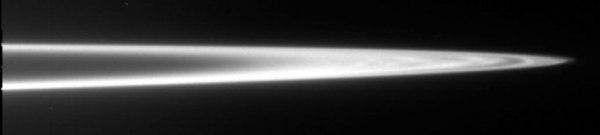

Jupiter's Rings

The ring system of Jupiter was imaged by the Galileo spacecraft on November 9, 1996. In this image the west ansa of Jupiter's main ring is seen at a resolution of 24 kilometers per pixel. The ring clearly shows radial structure that had only been hinted at in the Voyager images. The plot of the brightness of ring as a function of location, going from the inner-most edge of the image to the outer-most through the thickest part of the ring, shows the "dips" in brightness due to perturbations from satellites. Two small satellites, Adrastea and Metis, which are not seen in this image, orbit through the outer portion of the ansa; their location relative to these radial features will be available after further data analysis. The ring's faint halo is seen to arise in the inner main ring just as it fades. Although most of Jupiter's ring is composed of small grains that should be highly perturbed by the strong Jovian magnetosphere, the ring's brightness drops abruptly at the outer edge.

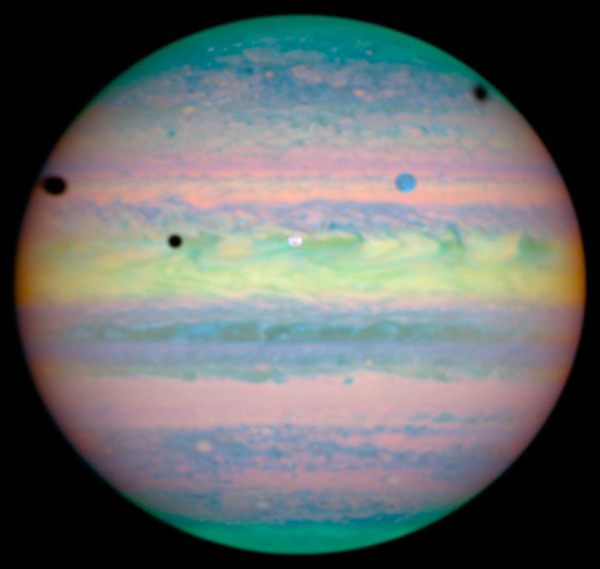

Rare Triple Eclipse on Jupiter

At first glance, Jupiter looks like it has a mild case of the measles. Five spots – one colored white, one blue, and three black – are scattered across the upper half of the planet. Closer inspection by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope reveals that these spots are actually a rare alignment of three of Jupiter's largest moons – Io, Ganymede, and Callisto – across the planet's face. In this image, the telltale signatures of this alignment are the shadows [the three black circles] cast by the moons. Io's shadow is located just above center and to the left; Ganymede's on the planet's left edge; and Callisto's near the right edge. Only two of the moons, however, are visible in this image. Io is the white circle in the center of the image, and Ganymede is the blue circle at upper right. Callisto is out of the image and to the right.

On Earth, we witness a solar eclipse when our Moon's shadow sweeps across our planet's face as it passes in front of our Sun. Jupiter, however, has four moons roughly the same size as Earth's Moon. The shadows of three of them occasionally sweep simultaneously across Jupiter. The image was taken March 28, 2004, with Hubble's Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer.

Seeing three shadows on Jupiter happens only about once or twice a decade. Why is this triple eclipse so unique? Io, Ganymede, and Callisto orbit Jupiter at different rates. Their shadows likewise cross Jupiter's face at different rates. For example, the outermost moon Callisto orbits the slowest of the three satellites. Callisto's shadow moves across the planet once for every 20 shadow crossings of Io. Add the crossing rate of Ganymede's shadow and the possibility of a triple eclipse becomes even more rare. Viewing the triple shadows in 2004 was even more special, because two of the moons were crossing Jupiter's face at the same time as the three shadows.

Jupiter appears in pastel colors in this photo because the observation was taken in near-infrared light. Astronomers combined images taken in three near-infrared wavelengths to make this color image. The photo shows sunlight reflected from Jupiter's clouds. In the near infrared, methane gas in Jupiter's atmosphere limits the penetration of sunlight, which causes clouds to appear in different colors depending on their altitude. Studying clouds in near-infrared light is very useful for scientists studying the layers of clouds that make up Jupiter's atmosphere. Yellow colors indicate high clouds; red colors lower clouds; and blue colors even lower clouds in Jupiter's atmosphere. The green color near the poles comes from a thin haze very high in the atmosphere. Ganymede's blue color comes from the absorption of water ice on its surface at longer wavelengths. Io's white color is from light reflected off bright sulfur compounds on the satellite's surface.

In viewing this rare alignment, astronomers also tested a new imaging technique. To increase the sharpness of the near-infrared camera images, astronomers speeded up Hubble's tracking system so that Jupiter traveled through the telescope's field of view much faster than normal. This technique allowed scientists to take rapid-fire snapshots of the planet and its moons. They then combined the images into one single picture to show more details of the planet and its moons.

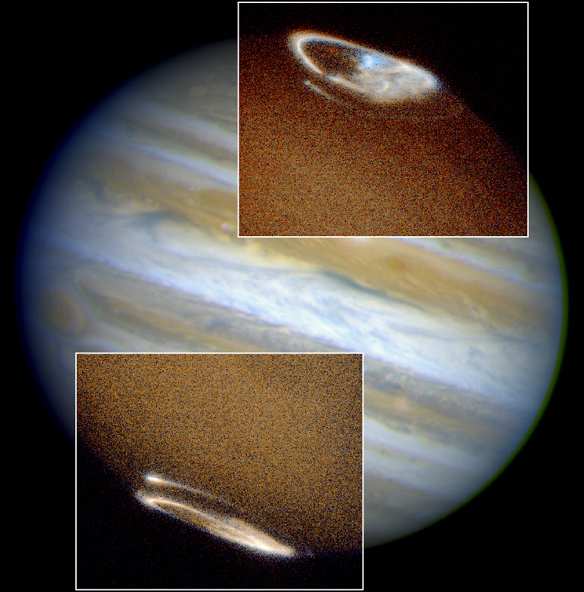

Jupiter’s Auroras

Images taken in ultraviolet light by the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) show both auroras, the oval-shaped objects in the inset photos. While the Hubble telescope has obtained images of Jupiter’s northern and southern lights since 1990, the new STIS instrument is 10 times more sensitive than earlier cameras. This allows for short exposures, reducing the blurring of the image caused by Jupiter’s rotation and providing two to five times higher resolution than earlier cameras. The resolution in these images is sufficient to show the “curtain” of auroral light extending several hundred miles above Jupiter’s limb (edge). Images of Earth’s auroral curtains, taken from the space shuttle, have a similar appearance. Jupiter’s auroral images are superimposed on a Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 image of the entire planet. The auroras are brilliant curtains of light in Jupiter’s upper atmosphere. Jovian auroral storms, like Earth’s, develop when electrically charged particles trapped in the magnetic field surrounding the planet spiral inward at high energies toward the north and south magnetic poles. When these particles hit the upper atmosphere, they excite atoms and molecules there, causing them to glow (the same process acting in street lights).

The electrons that strike Earth’s atmosphere come from the sun, and the auroral lights remain concentrated above the night sky in response to the “solar wind,” as Earth rotates underneath. Earth’s auroras exhibit storms that extend to lower latitudes in response to solar activity, which can be easily seen from the northern U. S. But Jupiter’s auroras are caused by particles spewed out by volcanoes on Io, one of Jupiter’s moons. These charged particles are then magnetically trapped and begin to rotate with Jupiter, producing ovals of auroral light centered on Jupiter’s magnetic poles in both the day and night skies. Scientists are comparing the Hubble telescope images with measurements taken by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft of Jupiter’s magnetic field and co-rotating charged particles. They believe the data will help them understand the production of Jupiter’s auroras.

Both auroras clearly show vapor trails of light left by Io. These vapor trails are the white, comet-shaped streaks just outside both auroral ovals. These streaks are not part of the auroral ovals. They are caused when an invisible electrical current of charged particles (equal to about 1 million amperes), ejected from Io, flow along Jupiter’s magnetic field lines to the planets north and south magnetic poles. This enormous current produces a bright but localized aurora where it enters Jupiter’s atmosphere at both magnetic poles. The brightest part of both emissions (on the left in both images) pinpoints where Io’s magnetic field lines leave its footprint on the planet. The trail of light following both emissions extends to the right all the way to Jupiter’s edge and represents the most sensitive detection of ultraviolet emissions from Jupiter to date. These emissions are related to magnetically trapped ions and electrons that are carried by Jupiter’s magnetic field along Io’s orbital path, and some of these charged particles continue to be driven down into Jupiter’s atmosphere for several hours after Io has passed by.

The images were taken Sept. 20, 1997. The artificial colors used here have been constructed by combining images taken in two different ultraviolet band passes, with one ultraviolet color presented as blue and the other as red. In this color representation, the planet’s reflected sunlight appears brown, while the auroral emissions appear white or shades of blue or red.

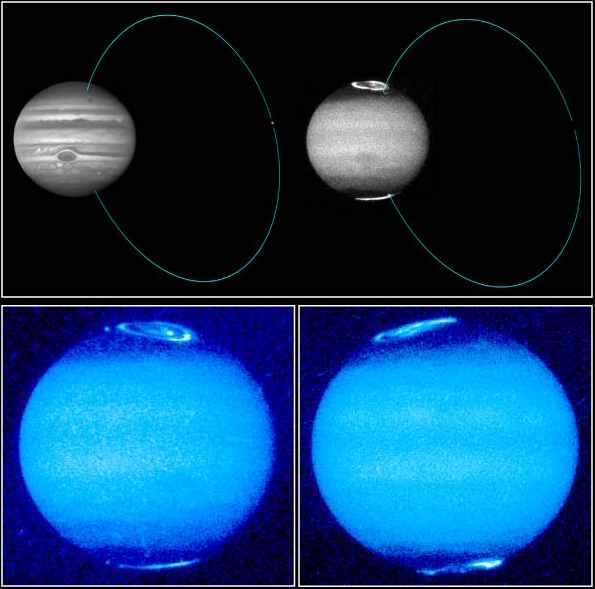

Jupiter’s Auroras and Io

These images, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, reveal changes in Jupiter’s auroral emissions and how small auroral spots just outside the emission rings are linked to the planet’s volcanic moon, Io. The images represent the most sensitive and sharply-detailed views ever taken of Jovian auroras.

The top panel pinpoints the effects of emissions from Io, which is about the size of Earth’s moon. The black-and-white image on the left, taken in visible light, shows how Io and Jupiter are linked by an invisible electrical current of charged particles called a “flux tube.” The particles - ejected from Io (the bright spot on Jupiter’s right) by volcanic eruptions - flow along Jupiter’s magnetic field lines, which thread through Io, to the planet’s north and south magnetic poles. This image also shows the belts of clouds surrounding Jupiter as well as the Great Red Spot.

The black-and-white image on the right, taken in ultraviolet light about 15 minutes later, shows Jupiter’s auroral emissions at the north and south poles. Just outside these emissions are the auroral spots. Called “footprints,” the spots are created when the particles in Io’s “flux tube” reach Jupiter’s upper atmosphere and interact with hydrogen gas, making it fluoresce. In this image, Io is not observable because it is faint in the ultraviolet.

The two ultraviolet images at the bottom of the picture show how the auroral emissions change in brightness and structure as Jupiter rotates. These false-color images also reveal how the magnetic field is offset from Jupiter’s spin axis by 10 to 15 degrees. In the right image, the north auroral emission is rising over the left limb; the south auroral oval is beginning to set. The image on the left, obtained on a different date, shows a full view of the north aurora, with a strong emission inside the main auroral oval.

The images were taken by the telescope’s Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 between May 1994 and September 1995.

Satellite Footprints Seen in Jupiter Aurora

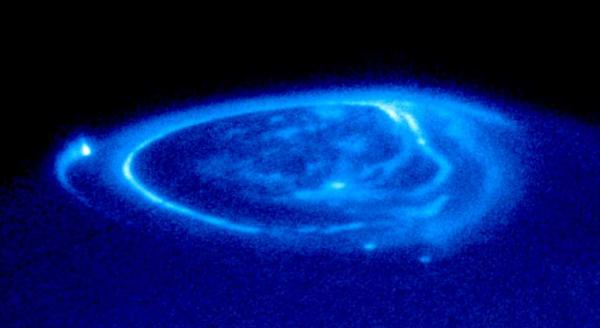

This is a spectacular NASA Hubble Space Telescope close-up view of an electric-blue aurora that is eerily glowing one half billion miles away on the giant planet Jupiter. Auroras are curtains of light resulting from high-energy electrons racing along the planet's magnetic field into the upper atmosphere. The electrons excite atmospheric gases, causing them to glow. The image shows the main oval of the aurora, which is centered on the magnetic north pole, plus more diffuse emissions inside the polar cap.

Though the aurora resembles the same phenomenon that crowns Earth's polar regions, the Hubble image shows unique emissions from the magnetic "footprints" of three of Jupiter's largest moons. (These points are reached by following Jupiter's magnetic field from each satellite down to the planet).

Auroral footprints can be seen in this image from Io (along the left hand limb), Ganymede (near the center), and Europa (just below and to the right of Ganymede's auroral footprint). These emissions, produced by electric currents generated by the satellites, flow along Jupiter's magnetic field, bouncing in and out of the upper atmosphere. They are unlike anything seen on Earth.

This ultraviolet image of Jupiter was taken with the Hubble Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) on November 26, 1998. In this ultraviolet view, the aurora stands out clearly, but Jupiter's cloud structure is masked by haze.

December 14, 2000 inaugurates an intensive two weeks of joint observation of Jupiter's aurora by Hubble and the Cassini spacecraft. Cassini will make its closest approach to Jupiter enroute to a July 2004 rendezvous with Saturn. A second campaign in January 2001 will consist of Hubble images of Jupiter's day-side aurora and Cassini images of Jupiter’s night-side aurora, obtained just after Cassini has flown past Jupiter. The team will develop computer models that predict how the aurora operates, and this will yield new insights into the effects of the solar wind on the magnetic fields of planets.

CosmicLight.com Home

CosmicLight.com Home