Vietnam Central Highlands, 1971 The following article was in the October 1971 issue of TYPHOON magazine (Vol. V, No. 3), an "in-country rag." from the inside cover:

|

|

ONE WHO REMEMBERS

Basci Hakkah

Life for the Koho tribesmen in the mountainous regions around Dalat is rugged. Montagnard infants who suckle a dry breast learn quickly that things do not come easy in the mountains. The children develop as their defense an ability to accept hardship and to appreciate intensely those good things that do come their way.

Dr. James Turpin is one of those good things. Through his Project Concern, a non-denominational, charity medical organization which he founded, he has brought to the montagnard people of the area around Elephant Mountain the realization that all hardship does not have to be endured. While the organization is international both in its scope of operation and the nationality of its staff, it was founded with the single hope of alleviating some of the suffering of the world's poor.

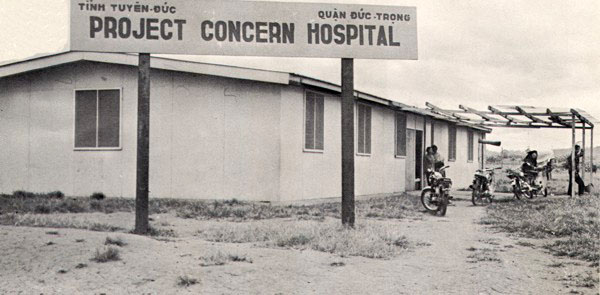

On the outskirts of Dalat, in the highlands, Dr. Turpin and Project Concern workers have established a hospital and dispensary for people who until recently did not realize that such a thing as medicine existed. Today, a handful of dedicated volunteers -- part of the 160 volunteers from 25 countries who staff Project Concern worldwide -- are training the Kohos to staff and maintain the medical facilities.

This sizeable task began in Vietnam in 1964 when Dr. Turpin built a dispensary for the people of Da Mpao, a small Koho village at the southern end of the Ho Chi Minh trail. Formerly a U.S. Special Forces camp, Da Mpao lies on the beautiful if inappropriately-named Dung River.

When the doctor arrived there, he saw that the villagers suffered from the same diseases as starving people the world over: acute malnutrition, skin lesions and a variety of respiratory ailments. The only difference was the severity of the situation. In his book Vietnam Doctor in which Dr. Turpin tells of his work with the Kohos he notes, "Here was a need far beyond any I had ever before seen, a need for kindness and sympathy and love as well as for medical treatment."

|

Training Program

In addition to treating the villagers of Da Mpao, Dr. Turpin and his staff initiated a training program for local Vietnamese and the montagnards to enable them to extend the geographical reach of medical assistance and to insure that the people could keep themselves healthy after the volunteers had gone. The instruction was provided by the Project Concern staff and classes were held six days a week for six months.

The instructors came to realize that the biggest obstacles to overcome were not the students' desire or ability to learn but their continued adherence to old tribal superstitions. Even after months of classes many students would continue to rely on trinkets to frighten away the spirits which caused headaches or other minor ailments.

But the students were eager to learn and after a period of time they became competent enough to diagnose and treat most illnesses themselves. After the completion of the specified course of study, the students became Village Medical Assistants (VMA) or Hospital Medical Assistants (HMA) depending on their occupational specialties.

The foresight of Dr. Turpin in establishing this training program became evident in 1968 when Viet Cong harassment in the area increased steadily. It was in that year that the Project Concern workers realized the security situation was such that they could no longer live at Da Mpao. After a dispensary facility was destroyed by the VC, operation of the other medical facilities was turned over to the VMA and HMA of the village while the Project Concern personnel provided support through frequent though unscheduled day visits.

While Project Concern was facing setbacks in one area, it was making advances in another. The staff which left Da Mpao was relocated in another hospital complex in the Dalat area. At Lien Hiep in the Duc Trong district, a six building complex was built by Project Concern with money donated by the Vernon Hill American Legion Post of Worcester County, Massachusetts. It was the wish of the Gold Star mothers and wives of that area (women who had lost their men in the Vietnam war) that the memorial which was to be constructed be a living one. Following a routine visit by Dr. Turpin to the area seeking donations for Project Concern, it was decided that the funds collected by the American Legion post should go to construct a hospital in the Dalat area.

The total cost of the complex came to $150,000. But this sizeable amount went primarily for medical equipment and not for actual building construction. In fact, the six buildings that make up the Project Concern facility at Lien Hiep are simple plywood structures.

Lien Hiep: simple plywood structures housing $150,000 worth of equipment

Compares Well

The extraordinary aspect of this facility is the sophisticated medical equipment available. This small hospital compares well with most in Vietnam and its equipment together with the personal and professional dedication of the 14-member staff have made the operation a success.

In addition to the sophisticated medical equipment at Lien Hiep, the hospital has its own water purification system. Water drawn from a nearby river is filtered prior to its entry into the six-building complex. The Lien Hiep hospital also has its own kitchen and dining area. Food is prepared for both the staff and the patients, free of charge. Although some of the rations are donated by nearby U.S. military units, most of it is purchased by the hospital with Project Concern funds.

Each week women staffers travel to the market at Dalat to buy fruit, vegetables and other staples for the coming week. If adapting to the diet of the Vietnamese is a hardship for the volunteers, this inconvenience is lessened by the fact that Dalat has some of the most delicious fruits and vegetables in the country. The rich fertile land and the cool temperate climate combine to make the Dalat area the "vegetable bowl" of Vietnam.

Early in the morning the montagnard villagers begin arriving at Lien Hiep. Some come from neighboring villages while others travel many miles to the hospital for medical attention. The volunteers point out that one of the problems of their montagnard patients is that they wait too long before coming in for treatment.

Many diseases which might have been curable in their early stages are terminal by the time the doctors get to diagnose them. In addition many have a tendency to stop taking medicine as soon as they feel better, not realizing that they are highly susceptible to relapse in the early stages of recovery.

Those patients who are able are requested to make payment for their treatment. First visits cost 300 piaster. Each new patient is given an identification card which he is to show on subsequent visits to the hospital. If patients do return for additional treatment at any time in the future, the cost is reduced to 200 piaster.

In addition to helping defray the cost of maintaining the hospital, the small fee enables the patient to uphold a certain sense of dignity. This is especially important to the montagnards, who are likely to shy away from handouts. Of course no one is ever turned away for inability to pay, but this token payment has proven to be indispensable at times.

In the early days of the operation of Da Mpao dispensary, a shortage of funds threatened to shut down the complex. At times the volunteer workers had so little money that they could not even buy food for themselves. It was only through the token payments of the montagnards, usually foodstuffs, that the workers were able to stay at the village.

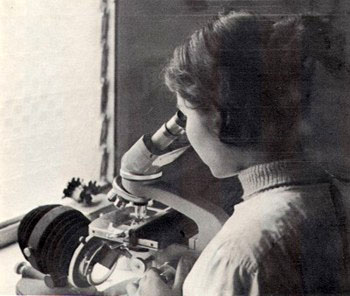

After the patients have arrived at the Lien Hiep hospital and have made their payment, they are directed by hospital medical assistants to rooms along a corridor where diagnosis or treatment begins. The hallway is usually crowded with families of patients and it is sometimes difficult to get from one room to another. In addition to an emergency room this section of the hospital has a laboratory , where blood and urine samples are evaluated, a pharmacy, an X-ray room and an operating room. Moreover, there is a maternity ward in the adjacent building.

These facilities, although rudimentary to most Americans, are nothing short of amazing to the mountain villager who benefits from them. Even the staffers remark that it is gratifying to be able to work with such excellent equipment.

But the Lien Hiep hospital complex is not without its problems. Viet Cong terrorism has caused a drastic cutback in services at Lien Hiep. In June, one of the female workers was killed in a rocket attack on the complex. As was the case in Da Mpao, the volunteers were forced to leave their hospital quarters for a more secure area.

This relocation has caused a severe reduction in the hospital's operation. Since there is only limited professional medical supervision at Lien Hiep, the hospital has gradually assumed the role of a day clinic. The maternity ward is now closed and surgery is no longer performed. All medical problems which are not out-patient in nature are referred to the already overcrowded Dalat Hospital. Part of the staff now works at the Dalat Hospital or makes visits to local villages.

But the staff continues to maintain a certain degree of optimism in spite of the current hardships. Dr. Turpin, who spends most of his time in the United States trying to raise funds for Project Concern, is expected to return in November. Bacsi Hakkah, ("the doctor who remembers us"), as he is called by the villagers, must at that time make the decisions which will determine the future of the project in Vietnam.

The volunteers draw encouragement from the successes they have had in the past as well as from the progress the Hospital and Village Medical Assistants are having. Fortunately, for those who need comparatively expensive medical attention but live on meager money pouches, the Project Concern volunteers view their present difficulties as just another hurdle in their efforts to bring health to the poor peoples of the world.

Understanding the Montagnards

Montagnard lifestyles are simple, and disease easily reaches epidemic proportions in highlands villages where water used for cooking and drinking is fetched (above) from nearby streams that may be polluted by other villages upstream.

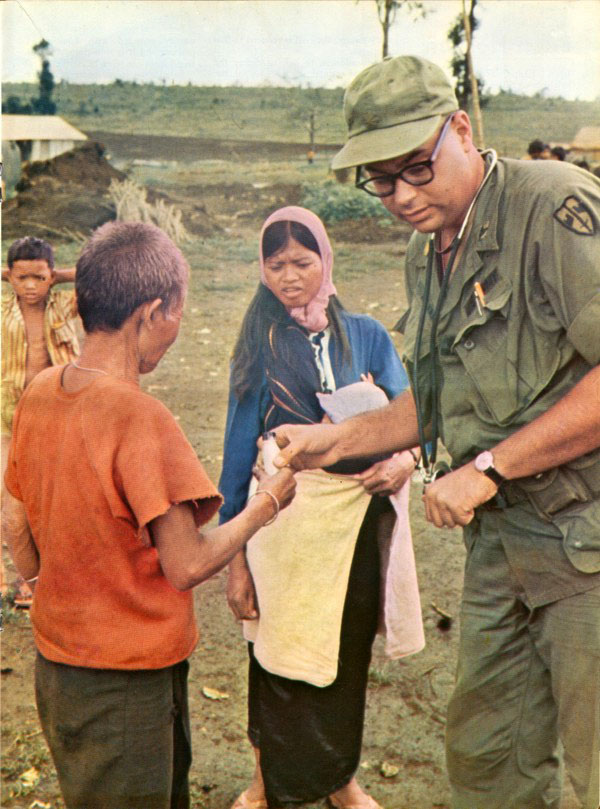

Project concern volunteers sometimes venture out from the hospitals to the villages in teams to provide medical assistance to the montagnards, the same as some of their military counterparts (below). A middle-aged Bahnar tribesman (left) watches fellow villagers with typical interest and curiosity as they receive medicine and inoculations. His pipe is made of 50-caliber machine gun rounds.